Las lluvias regresaron con fuerza. Después de una mega-sequía de 12 años, el invierno de 2023 ha registrado más precipitaciones que en años anteriores, incluyendo un evento de lluvia extremo a fines de junio de 2023. Se estima que cerca de diez mil personas resultaron afectadas por las inundaciones, incluyendo desplazamientos forzados, pérdida de hogares, la interrupción de servicios básicos como agua potable y electricidad. Además, se registraron varios fallecidos como resultado directo de las inundaciones.

El impacto más significativo de las lluvias se observó en las áreas cercanas a las montañas, la precordillera y la cordillera de la zona central (33-38ºS, Fig. 1a). Mientras que en los valles, ciudades como Santiago registraron menos de 50 mm de lluvia entre el 22 y el 26 de junio, en áreas de mayor altitud se superó los 400 mm (1, Vismet). El récord lo tiene la estación ubicada en el Embalse Bullileo, que registró impresionantes 850 mm. Las estaciones en la superficie confirman el máximo de precipitaciones estimado por el reanálisis ERA5 entre los 35 y 38ºS, correspondiente a las regiones del Maule, Ñuble y Biobío (en la Fig. 1a, área marcada con colores rojos intensos).

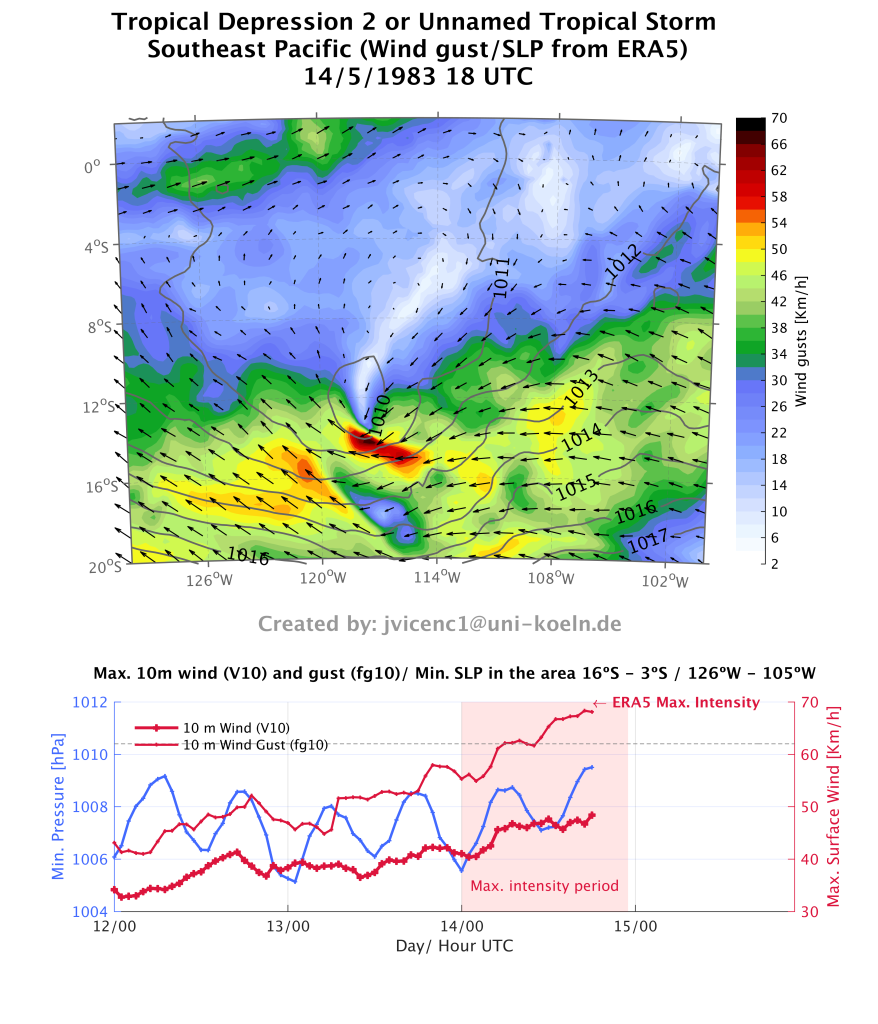

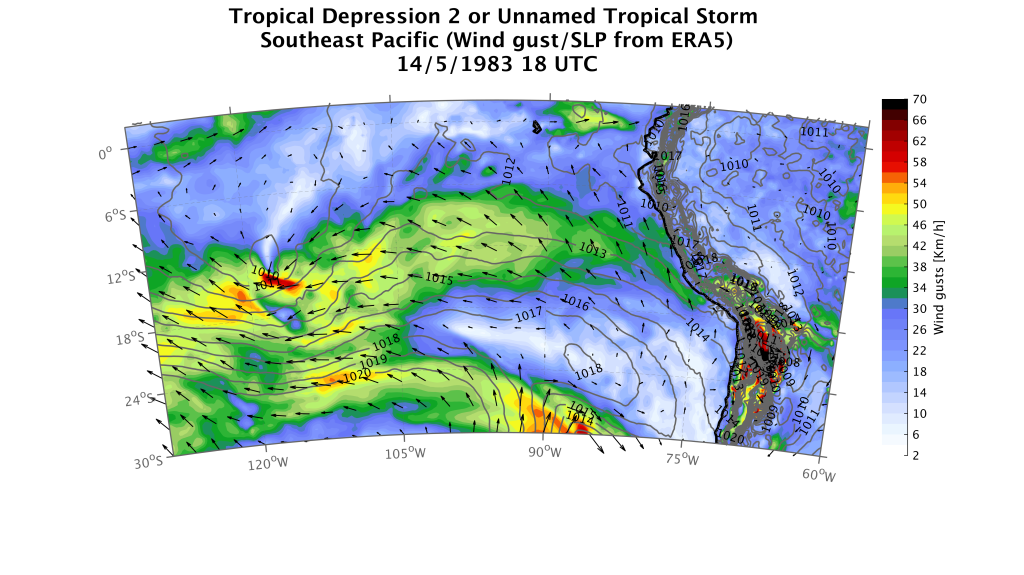

Una de las características principales de este episodio de precipitaciones a nivel sinóptico es la formación de un carrusel de bajas presiones sobre el Pacífico Sureste (marcadas con la letra «L» en la Figura 1b), moviéndose lentamente hacia el oeste y permitiendo el transporte de humedad de forma continua durante varios días desde el Pacífico Central.

El Transporte Integrado de Vapor (IVT, por sus siglas en inglés), utilizado para medir la intensidad de los ríos atmosféricos, alcanzó a lo largo de la costa de Chile Central entre ~500 y 960 kg m-1 s-1, suficiente para catalogarlo al menos como un evento moderado (categoría 3 o 4).

El resultado del transporte de humedad se expresa con una larga y extensa columna de alto contenido de vapor de agua (IWV por sus siglas en inglés) con valores >30 mm frente a la región central de Chile (Fig. 1d) y que están muy alejados de la media climatológica de invierno (~10 mm).

Otro factor importante es el ángulo del flujo del viento del oeste. Al chocar directamente con la cordillera en un ángulo de aproximadamente 90°, estas tormentas suelen generar abundantes lluvias en períodos prolongados, ya que el ascenso del aire se produce principalmente debido a la abrupta topografía de la zona central (Falvey y Garreaud, 2). La región experimentó cerca de 5 días consecutivos con un fuerte flujo de humedad desde el oeste, provocando tasas de precipitación en la precordillera de entre 5 y 20 mm/hr según datos de estaciones y reanálisis.

Asociado a esto, la isoterma 0ºC se mantuvo entre 3000-3200 metros sobre el nivel del mar (msnm) en las regiones de Valparaíso a O’Higgins (33-35ºS) y entre 2750-3250 msnm en las regiones de El Maule, Ñuble y Bioíbo (35-38ºS) de acuerdo a ERA5 (Fig. 1c). Estos valores son confirmados por los radiosondeos diarios en Santo Domingo (33.6ºS) que registraron una altura media entre 3100-3300 msnm (3, Campos). La presencia de una isoterma alta dio como resultado abundantes lluvias en las zonas altas de la cordillera, desencadenando rápidas crecidas de ríos, deslizamientos de tierra e inundaciones valle abajo. Esta situación fue probablemente parcialmente favorecida por el fenómeno de lluvia sobre nieve, particularmente al inicio del evento (4, Garreaud)

¿Lluvia, isoterma 0ºC o algo más?

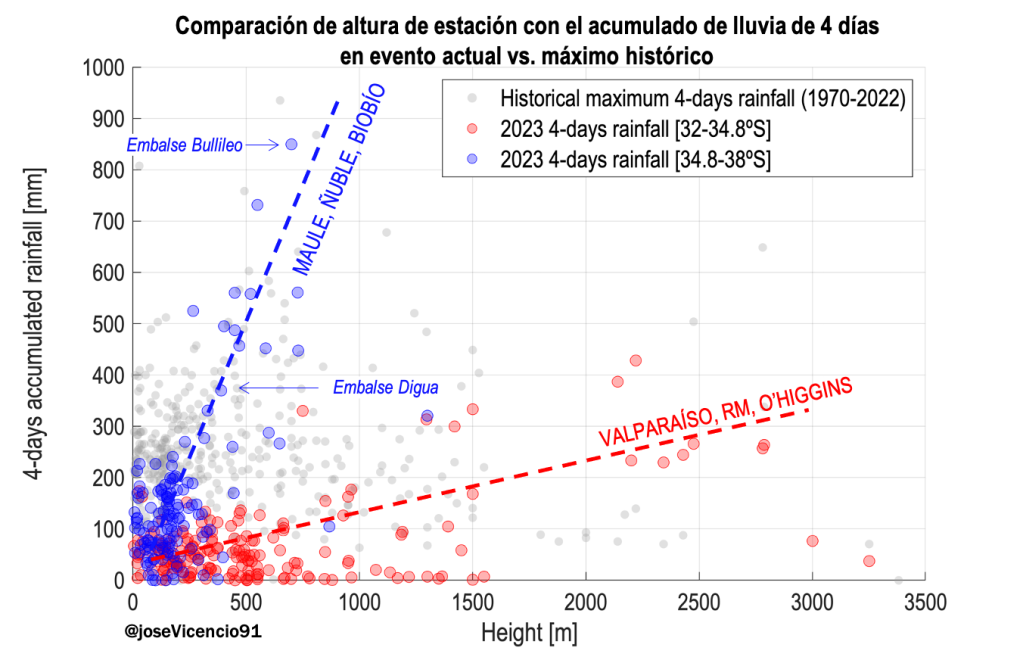

Estos niveles extraordinarios de precipitación son poco comunes y solo se han registrado en un par de ocasiones en las estaciones ubicadas en áreas de pie de monte y precordillera. Por ejemplo, en altitudes entre 500 y 1000 msnm, los acumulados máximos de lluvia en un período de 4 días superiores a los registrados en el Embalse Bullileo en 2023 solo se han observado en 2 estaciones en los últimos 50 años (Fig. 2)

El incremento de la precipitación con la altitud es notable en las regiones desde Maule hasta Biobío (35-38°S), donde los acumulados pasan de 100 a 700 mm en tan solo 0.5 km de elevación. Esto confirma que la zona experimentó el mayor impacto tanto en términos de cantidad de lluvia como en el aumento del caudal de ríos e inundaciones (Fig. 2).

En las regiones de Valparaíso, Metropolitana y O’Higgins (33-35ºS), donde el río atmosférico impactó con menos intensidad, el gradiente vertical de precipitación es menos pronunciado (Fig. 2). No obstante, este evento se destaca por registrar precipitaciones significativas (200-400 mm) sobre los 2000 msnm, una altitud en la que normalmente se presentaría precipitación en forma sólida.

Como mencionamos anteriormente, un factor crucial de este evento ha sido la altura de la isoterma 0ºC, la cual osciló entre los 2700 y 3200 msnm en la zona central. Los datos históricos analizados por la Dirección Meteorológica de Chile (DMC) utilizando el radiosonda de Santo Domingo (Vásquez, 5) indican que este evento se encuentra dentro del rango intercuartil para los días de lluvia (es decir, dentro del rango normal esperado para junio), aunque en su extremo superior (representado por el triángulo rojo en la Figura 3).

En este sentido, parece que este evento ha estado más influenciado por la extrema cantidad de precipitación y su duración que por la altura de la isoterma de 0°C. No obstante, esta hipótesis debe ser respaldada por análisis más detallados, especialmente teniendo en cuenta la distancia entre el radiosonda y la zona de mayor impacto del río atmosférico

Lluvias históricas

Para complementar el análisis tomamos la estación de Embalse Digua, ubicada en el corazón de la precordillera de la Región del Maule y que posee un registro histórico continuo al menos desde 1970. Al calcular los eventos de lluvia acumulada en un período de 4 días, encontramos que el registro de 2023 (369.5 mm) se sitúa entre los valores más extremos de toda la serie, superado únicamente por otros dos eventos de mayor intensidad en los últimos 50 años (Tabla 1).

| Ranking | Acumulación en 4 días | Fecha* |

| #1 | 407.1 mm | 21-05-2008 |

| #2 | 389.0 mm | 08-05-1972 |

| #3 | 369.5 mm | 26-06-2023 |

| #4 | 291.9 mm | 28-05-2001 |

| #5 | 287.7 mm | 05-05-1992 |

| Media Anual | 1334.4 mm | 1991-2020 |

En 1972, un evento similar se observó a lo largo de la zona central, con lluvias totales sobre 500 mm en la precordillera entre 35 y 37ºS según las estaciones meteorológicas y hasta 300 mm según ERA5 (Fig. 4a).

La sinóptica asociada a ese evento (Fig. 4c) es similar al de 2023, mostrando un extenso sistema frontal asociado a una baja presión (L) en el medio del océano Pacífico junto a una Alta presión bien desarrolla al sur de 50ºS. Este patrón induce transporte de humedad desde el Pacífico hacia Chile Central, fenómeno conocido como tormentas cálidas (Garreaud, 6). El río atmosférico aterrizó con intensidades superiores a 500 kg m-1 s-1, muy similar a lo observado este 2023. Adicionalmente, la isoterma 0ºC se encuentra entre los 2700-3200 m sobre la zona de máximo de lluvia (Fig. 4b) y que también coincide bastante con el episodio de este año.

De acuerdo a los registros, no hubo inundaciones en el caso observado en mayo de 1972 a pesar de las similitudes con 2023. Esto es un desafío para los equipos encargados de pronosticar este tipo de emergencias, puesto que se tiende a utilizar eventos similares del pasado para predecir el futuro, ¿qué hace la diferencia entre ambos eventos meteorológicos?

Para comprender por qué dos eventos extremos de lluvia pueden tener resultados diferentes en términos de inundaciones, analizaremos la forma en que la altura de la isoterma cero y la intensidad de la lluvia evolucionaron a lo largo del tiempo en la zona Maule-Biobío antes y después del impacto del río atmosférico (Fig. 5).

En el evento de 1972, se observaron tasas de precipitación horaria más altas en comparación con 2023 (~6 vs. ~4 mm/hora). Sin embargo, esta alta intensidad de lluvia se concentró en un período de tiempo muy limitado, disminuyendo rápidamente después de aproximadamente 50 horas de aterrizaje del río (Fig. 5). El incremento de la isoterma de 0°C por encima de los 3000 msnm a partir de la hora ~70 estuvo acompañado de una baja intensidad de precipitación, lo que probablemente ocasionó una menor crecida de los afluentes de los ríos en la cordillera.

En junio de 2023, se observó que la intensidad de la lluvia se mantuvo constante durante aproximadamente 100 horas después del aterrizaje del río atmosférico, mientras que la isoterma de 0°C se mantuvo casi constante alrededor de los 3000 msnm. Esto sugiere que la distribución horaria de la lluvia también desempeña un papel crucial en la generación de una catástrofe similar a la que estamos experimentando actualmente.

Es importante tener en cuenta que los pronósticos de precipitación no solo deben considerar el acumulado total del evento en cuestión, sino también su distribución a lo largo del tiempo, es decir, la forma en que la lluvia se distribuye en términos de intensidad y como evolucionará durante el evento. Además, una buena estimación de la altura de la isoterma de 0°C y la sinóptica imperante son factores fundamentales para comprender y predecir los posibles impactos y riesgos asociados a las condiciones climáticas extremas.

En resumen, el evento de precipitación extrema en Chile Central se caracterizó por una isoterma de 0°C alrededor de los 3000 msm, la llegada de un río atmosférico con intensidades superiores a 500 kg m-1 s-1 (categoría 3 o superior) y un patrón sinóptico que mantuvo un flujo constante del oeste durante varios días. Estas condiciones provocaron lluvias históricas en la región, con intensidades horarias de más de 5-10 mm/hora durante aproximadamente 100 horas consecutivas, acumulando entre 400 y 850 mm en precordillera.

Escrito por: José Vicencio Veloso

Fuentes:

- (1) Datos observados de lluvia obtenidos a través de portal VISMET del CR2-U de Chile: https://vismet.cr2.cl

- (2) Wintertime Precipitation Episodes in Central Chile: Associated Meteorological Conditions and Orographic Influences Mark Falvey and René Garreaud: https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/hydr/8/2/jhm562_1.xml

- (3) Diego Campos en twitter: https://twitter.com/meteodiego/status/1672656415322693632/photo/1

- (4) Prof. Dr. René Garreaud en CR2.cl: https://www.cr2.cl/analisis-cr2-vuelven-los-gigantes-un-analisis-preliminar-de-la-tormenta-ocurrida-entre-el-21-y-26-de-junio-de-2023-en-chile-central/

- (5) Ricardo Vásquez, DMC: https://climatologia.meteochile.gob.cl/application/publicaciones/documentoPdf/isotermaCero/isotermaCero20200101.pdf

Extra bonus

Si has llegado leyendo hasta aquí, te dejo con las animaciones del evento completo considerando el IVT y el vapor de agua integrado.